The big issue that I ran into when trying to build on the last post was visibility culling. As you may have noticed, the live demo of the previous post wasn't exactly speedy, and that's because it was trying to render every piece of a very large scene every frame. The obvious next step is to introduce a visibility testing system that can quickly inform you of what meshes are potentially visible from a given point in the world. This isn't a new concept, and it's one that I've worked with before. Quake 3 and the Source engine both use a pretty straightforward PVS (potentially visible set) system, and I was expecting that Unity would expose similar information through it's APIs.

Unfortunately, it doesn't.

The information is all there, Unity actually generates it, but it doesn't provide a way to query it in an export process. This means that my options for speeding up the scene were:

- Create a parser that reads the (undocumented) native Unity format and extract the vis information from there (Um... no thanks.)

- Run the exported level through a post-process that generates it for me. This would involve breaking the scene up into sections and raycasting from section to section thousands of times to see if section A is visible from section B at any point.

I contemplated just skipping that step and working on other aspects like collision detection or expanding on the animation system, but the fact that I would have to work out that issue at some point in time meant that sidestepping it now would just make it that much more aggravating to return to later.

But, even more importantly, as I was pondering how to address all of that I started to have these creeping concerns about a major bottlenecks in my development.

Now, since I'm sure most of you reading this are programmers I know the word "bottleneck" immediately calls to mind things like Disk I/O, network bandwidth, and caches of various shapes and sizes. But it's actually not technical bottlenecks I'm referring to here. A bottleneck is really anything that slows down a process, wether that be a digital process or a human one. We've all dealt with that one guy that everything has to go through that's constantly overbooked or that stupid form you have to fill out that makes reporting bugs take 3 times longer than it should. They're all bottlenecks.

My personal bottleneck (at least at this point) is art resources. As you may have noticed most of the demos that I've done thus far have used resources from other games. In many ways I attribute a decent chunk of the success I've had in the WebGL space to this fact. There have been a lot of more technically impressive WebGL demos than mine, but the fact that I use recognizable scenes gives people a mental yardstick for what they're seeing.

There's a big huge gaping problem with that approach, though: I don't own any of the art that I use. The code, yes, but what it's rendering? No. My Quake 3 demo is online only because id graciously hasn't asked me to take it down. I'll never post a live version of my Rage or Source demos because I was asked not to, and I respect the content creators too much to go against their wishes. Even when I was playing with Unity, I was still relying on art resources that other people built to get by. That's an awkward position to be in.

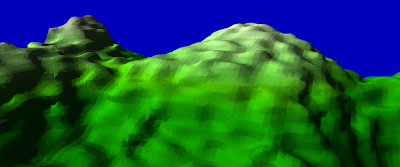

The solution? Create my own art, of course! But while I'm pretty confident that I could build a renderer capable of drawing this:

My artistic skills would probably yield a scene that looks like this:

And you know what? I don't even consider myself a bad artist! I've always enjoyed sketching, and while I'm not spectacular by any means I'd like to think I'm at least slightly above average:

But I'm well aware of my limits. My art tends to be simple and cartoony, it's kinda inconsistent in quality, and I'm not terribly good with mechanical drawings. It usually doesn't translate well into 3 dimensions either (at least not at my hands.) Point is: being "not terrible" with a pencil and paper doesn't translate into "good" in Maya. I could never hope to produce art of the quality that I've been using for my demos thus far in any practical quantity or timeframe.

The most obvious response to such a problem would be to recruit an artist who does actually have the skills needed to create a good looking scene. The issue there being that I would have no means with which to pay that individual for their services. I refuse to ask for someone else to lend me their talents if I can't compensate them in some tangible way.

Sidebar time!So, if I can't afford an artist and I'm not able to create detailed art myself I may as well just give up now, right?

Programmers: I see way too many posts online begging for artistic talent with no actual compensation. Don't do that. It's a horrible thing to do to another human being.

I know that you're planning on reimbursing them generously "when it's finished" but the cold hard truth of the matter is that your game will probably fail to ever materialize, especially if it's a first attempt. Don't feel bad about that! It's a critical part of the learning process to experience failure. Just don't drag some other poor soul into it. Do Asteroids. Do Pong. Do Tetris. Make sure you can actually complete something simple with art requirements well within your means. And when you finally do need an artist, pay them for their work with cash, not I.O.U's

Artists: The phrase "I can't pay you yet" in any of it's varied forms is your signal to run away. Don't ever allow yourself to be conned into giving your work away in exchange for a promise of a share of some mythical profits "when it's finished." If your work is good enough to be in any game it's good enough to be paid for when you do it, not when the other guy does his part.

Okay, Mini-rant is over.

Nope! Procedural generation to the rescue!

I may not be very good at tweaking vertices by hand, but I'm awesome at tweaking variables. It makes sense to use that to my advantage and put the computer to work doing my art for me! Obviously that doesn't work for everything, but there's an awful lot of things that can be very reasonably generated with a clever algorithm or two:

- Landscapes

- Trees, Grass, and Other Foliage

- Particle Effects

- Water

- Clouds

- Stars

- etc.

I'm sure this change of pace will disappoint some of my readers, since the end result won't be visually stunning. But I'm hoping that it will still look good regardless and it will allow me to move forward more confidently than before. I don't want to talk too much about my plans, since they may shift as the series goes on. And frankly I still feel I'm being a little too ambitious, but if any of this was easy it wouldn't be worth writing about, would it?

So some time in the next week or so, look forward to the next post in this series. We'll be talking about creating landscapes with perlin noise (kinda like Minecraft)! Hope to see you then!